This post is part of celebrating Women’s History month with 31 days of posts focused on improving the climate for social and gender equality in the children’s and teens’ literature community. Join in the conversation on Twitter #kidlitwomen or on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/kidlitwomen.

I hold a lot of privilege in our society. I am a White, cisgender, bisexual woman of French-Canadian and Irish descent. I’m in my forties, neurotypical, and I’m not disabled. Although I no longer formally practice a religion, I was raised Catholic and still feel some connection to that faith heritage. I grew up the eldest of three siblings in a middle-class family (Mom was an LPN, and Dad was a public school administrator), and I think that’s probably the best class descriptor for my family now, though economic insecurity nips at my heels as the primary breadwinner in a large, blended, adoptive, multiracial family that includes seven children ages 0-21.

I hold a lot of privilege in our society. I am a White, cisgender, bisexual woman of French-Canadian and Irish descent. I’m in my forties, neurotypical, and I’m not disabled. Although I no longer formally practice a religion, I was raised Catholic and still feel some connection to that faith heritage. I grew up the eldest of three siblings in a middle-class family (Mom was an LPN, and Dad was a public school administrator), and I think that’s probably the best class descriptor for my family now, though economic insecurity nips at my heels as the primary breadwinner in a large, blended, adoptive, multiracial family that includes seven children ages 0-21.

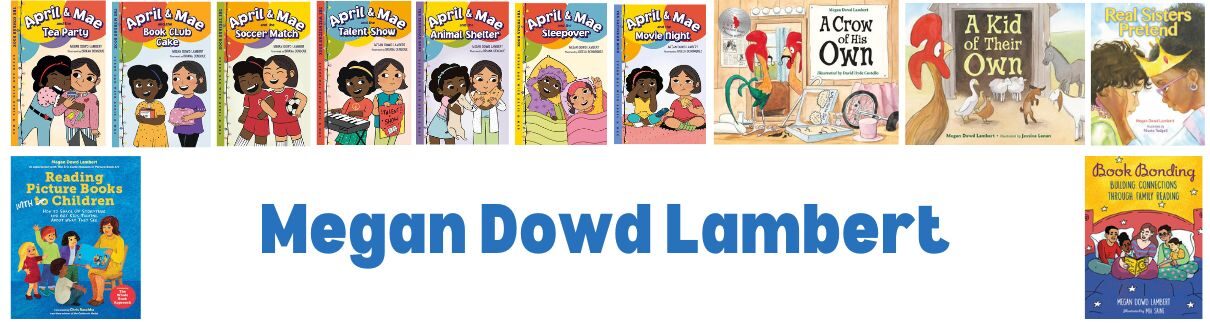

I share this personal information because I know that a majority of the people in the broad field of children’s literature are also White, cisgender women, and I’m committed to resisting the complacent comfort that could arise from that reality of my professional life. The status quo is exclusive and untenable, and so I must ask myself if I’m really walking the walk or just talking the talk of inclusivity as a Senior Lecturer in Children’s Literature at Simmons College, and as a reviewer and author, too. When Grace Lin invited me to write a post for #KidLitWomen, I wondered what I could contribute that would be helpful to readers also striving for inclusivity, no matter what they may or may not have in common with me, and I turned to an invaluable tool in my own self-reflective practice: the diversity audit.

Click here to read my full #KidLitWomen diversity audit post, which offers a model of a diversity audit and goals that arise from its results.