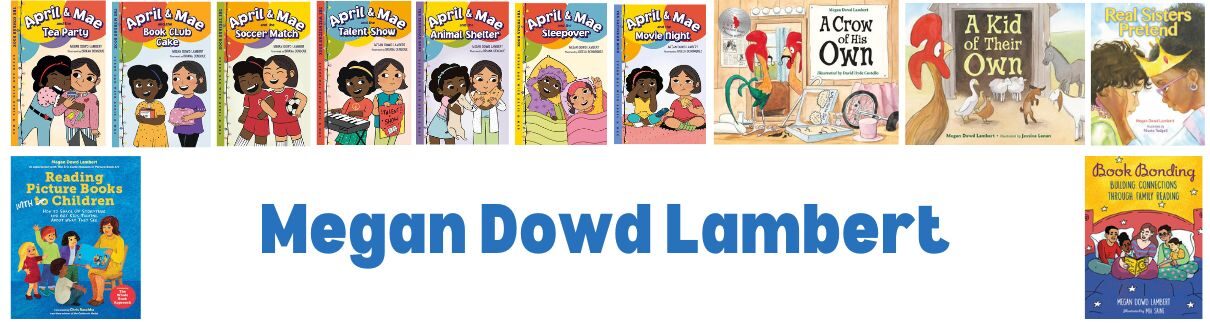

I’ve led thousands of storytimes over the course of my career, but as a new picture book author, so far only a handful of these have featured picture books I’ve written. A Crow of His Own illustrated by David Hyde Costello (Charlesbridge 2015) came out in April 2015, and I’ve had a great time reading it at area schools and libraries. Kids have responded to the wordplay and have also enjoyed hearing about the story’s playful origins in something that David calls “the scribble game.” Here’s what happened: When I told David I wanted to try to write a picture book text, he invited me to his studio and he drew a scribble that was just a little swoosh on a piece of paper and asked me,

“What does that look like?”

“A mustache,” I replied.

“Ok, then, who has a mustache?” he asked, and I replied with the first thing I thought of:

“A rooster!”

“So now you need to write a story about a rooster with a mustache,” David responded, and I did!

My newest picture book, Real Sisters Pretend (2016 Tilbury House Publishers), illustrated by Nicole Tadgell, just came out in May 2016, and its inspiration came from two of my daughters, whom I overheard playing and having a conversation about how adoption makes them “real sisters” even though they have different birth parents. This conversation arose after an incident at the grocery store when a stranger asked me (in front of them) “Are they real sisters?” in a tone lace with incredulity rather than friendly curiosity. I was so moved by how my daughters talked through their feelings and validated their bonds with one another, and I wrote this picture book to honor their sisterhood and to spark conversations about family diversity.

My newest picture book, Real Sisters Pretend (2016 Tilbury House Publishers), illustrated by Nicole Tadgell, just came out in May 2016, and its inspiration came from two of my daughters, whom I overheard playing and having a conversation about how adoption makes them “real sisters” even though they have different birth parents. This conversation arose after an incident at the grocery store when a stranger asked me (in front of them) “Are they real sisters?” in a tone lace with incredulity rather than friendly curiosity. I was so moved by how my daughters talked through their feelings and validated their bonds with one another, and I wrote this picture book to honor their sisterhood and to spark conversations about family diversity.

My whole family joined me and Nicole for our book launch at the Odyssey Bookshop, and my daughters who inspired the story even signed copies of the book since some of the words came from them.  They are both pretty shy, but they were so proud to join in that day, and I was proud of them, too. Out of respect for my children’s privacy I changed details about the characters’ names, adoption stories, as well as the family constellation (they have no other siblings in the book, Nicole didn’t use our family as models, and she depicted one of the adoptive moms as a Woman of Color), and I also injected princess play into the story just because I wanted to see brown girls wearing crowns in the illustrations. But the nurturing essence of the sisters’ close relationship remains the same because that’s what I wanted to center and honor in the book.

They are both pretty shy, but they were so proud to join in that day, and I was proud of them, too. Out of respect for my children’s privacy I changed details about the characters’ names, adoption stories, as well as the family constellation (they have no other siblings in the book, Nicole didn’t use our family as models, and she depicted one of the adoptive moms as a Woman of Color), and I also injected princess play into the story just because I wanted to see brown girls wearing crowns in the illustrations. But the nurturing essence of the sisters’ close relationship remains the same because that’s what I wanted to center and honor in the book.

I read the book aloud in fourth and fifth grade classes at my younger children’s elementary school this month, and the response was amazing. Not only were children interested in talking about thoughtful, kind ways of voicing curiosity about other people, they also wanted to talk about how to respond to others’ questions. One thing that came up is that it’s just plain good manners to get to know people at least a little bit before you start asking personal questions. We also talked about positive vocabulary that many people—adoptive parents, adoptees, and birthparents—advocate using, for example:

“Biological or birth or first family/mother/father/sibling/” instead of “real family/mother/father/sibling”

“Placed for adoption” instead of “gave up for adoption”

“How did you become a family?” instead of “Where’d you get them?”

And so on.

I was careful to validate the fact that asking questions is an important part of how we learn about the world around us, including the people who populate it. I also told kids that I was inviting their questions of me, but that I would respect my children’s privacy with regard to revealing specifics about their stories. Some of the children in these classrooms were also adopted, including some transracial adoptees with two moms, like my kids, and like the kids in my picture book. Other kids’ family constellations differed, and many children were moved to share stories of their own that my book made them think about.

A biracial girl who was not adopted and whose mother is White and father is Black started by saying that people often ask her if she is adopted when they see her with her mom. While she didn’t say that this hurt her, she said was very hurt when a person asked “Are those your parents?” and then said she “never should have been born” since she is mixed. Her classmates responded with compassion, kindness, and righteous anger. We talked about how the person who said this was racist and that their comment revealed a lot about them and their hatred and nothing about her and her worth. She smiled, and seemed to feel both affirmed and empowered, and then I shared the “ask back” strategy that a blogger who calls herself “Mother in the Mix” proposes to help kids respond to questions:

“Are you adopted?”

“Yes (or no). Are you?”

Or:

“Is that your real mom?”

“Yes. Is that your real mom?”

One child said, “But what if the person isn’t with a mom or someone else?”

“Well,” I started, “I guess you could still ask back something like, “Yes. Are those your real shoes?”

And everyone laughed. It’s a little cheeky, but I like how this approach empowers kids since personal questions, depending on phrasing and tone, can feel disempowering. The ask back strategy levels the conversation, asserting the position of both parties to a conversation as subjects and not just objects of curiosity.

Many other children shared stories, too. When I talked about how one of the girls in my picture book has a toy from her birthmom because some adopted children do have memories, or gifts, or ongoing relationships with their birth families, a girl spoke of being raised by her grandmother, but still getting to see her mom. “I never met my dad, but I see people in his family sometimes. I still don’t know a lot about them,” she said.

“My aunt was adopted when she was a baby, and when she was a grown-up she met her mom—I mean her birthmom,” another boy said.

“And that’s what can happen as you grow up,” I said, “You can learn more and more about yourself and your history and your family, and then you can share what you want to and keep private what you want to.”

In another classroom, a child who is transracial adoptee from India with two white moms kept subtly signing what I quickly figured out was the ASL sign for “same” or “me too.”

“You don’t owe anyone a response,” I said at one point when we were talking about the ask-back strategy. “It’s perfectly ok to say that you don’t want to talk about your own story if you don’t want to because it’s yours.” (same)

“Racism is learned, and so it can be unlearned, but it’s not your job to teach people, especially since you are children.” (same)

“There can be happy parts about adoption, but there can also be lots of sad parts and lots of questions that adoptees have.” (same).

In one classroom lots of White kids who are not adoptees started talking about being asked if they were adopted since they look different from other people in their family, “Just because I have blond hair and no one else does,” said one boy.

“Me too!” came responses from other kids.

These responses had the seeds of empathy within them, but I also used them to underscore that adoption isn’t something to be ashamed of, so the question or its underlying assumption shouldn’t be regarded as an insult. We also talked about how finding common ground with someone across differences (regarding race, adoptive status, or other parts of one’s identity) can be a show of support, but that listening to others’ experiences without then bringing in your own can demonstrate concern and respect by refusing to center oneself.

Ultimately, my discussions with children about family diversity reminded me of what one of my favorite writers, Andrew Solomon calls “the ecosphere of kindness” when he writes: “I don’t accept subtractive models of love, only additive ones. And I believe that in the same way that we need species diversity to ensure that the planet can go on, so we need this diversity of affection and diversity of family in order to strengthen the ecosphere of kindness.” During my author visit I saw before me diverse groups of children doing their part to strengthen that ecosphere of kindness as they listened to one another, shared their own stories, and talked through their ideas about how treat themselves and each other with kindness and compassion. I am eager to keep sharing my book and look forward to hearing from readers about their experiences with it. My hope is that it will be affirming for children who find parts of their own stories in its pages, and that it will also help spark conversations in libraries, classrooms, and homes about family diversity.