This post is part of celebrating Women’s History month with 31 days of posts focused on improving the climate for social and gender equality in the children’s and teens’ literature community. Join in the conversation on Twitter #kidlitwomen or on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/kidlitwomen.

Here’s how I found the time to revise this #KidLitWomen piece, not at the kitchen table, but in bed beside my sleeping baby.

I’ve been trying to revise this #KidLitWomen post about time management as a writing mother, for weeks. But, all too fittingly, I’ve been unable to find the time! And as I joked about this with my husband and negotiated how, today, we would juggle his need for time to work on grad school assignments, my need to focus on various writing projects, and the needs of our children, I remembered a profile of the poet Lucille Clifton by Elizabeth Alexander that ran in the New Yorker soon after Clifton died in 2010. Alexander writes,

Clifton had six children and made poems not in “a room of one’s own” but, rather, at the proverbial kitchen table, with family life proceeding around her. “Why do you think my poems are so short?” she would often say, with a laugh, when people would ask how she managed to write so many books.

In addition to poetry, Clifton also wrote picture books (including the groundbreaking, and, sadly, mostly out-of-print Everett Anderson series) so we in the #KidLitWomen community can proudly claim her as part of our history. I haven’t yet written “so many books,” and I marvel at Clifton’s humility in describing her brilliant, spare poems as merely “so short,” but I find true kinship with her as a writing mother in a large family. My seven children range in age from 5 months-old to nearly 21-years-old, and I appreciate Clifton’s good-humored response to inquiries about what some might call “work-life balance.” I’ve never much liked this term because when I separate “work” and “life” onto a metaphorical, two-sided scale, the goal of achieving balance feels like a set-up for failure. I fear I’ll never measure up, or like there’s not enough of me to go around. And don’t get me started on “a room of one’s own,” which, metaphorical or not, strikes me as an ideal that risks erasing the creative genius and tenacity of so many people, including mothers, who’ve made art without such space afforded them.

In contrast, Clifton’s “proverbial kitchen table, with family life proceeding around her” evokes a creative life that doesn’t seek to balance separate spheres of work and life, so much as to accommodate the overlapping of the two. I’d be a very different writer, indeed, if I weren’t a mother since much of my writing about children’s literature arises from shared experiences of reading with my kids, and my newer forays into writing children’s books of my own are greatly informed by their lives and interests. This is an ideal I can aspire to, even if I don’t consistently achieve such happy integration of work and life.

But now, and without leaving the kitchen, I want to poke a bit at the notion of “life” as a catch-all category in opposition to “work.” And to do so, I’ll get up from Clifton’s table and make my way to a metaphorical stovetop, described in this essay by David Sedaris, whose friend asked him to imagine a stove with four burners:

This was not a real stove but a symbolic one, used to prove a point at a management seminar she’d once attended. “One burner represents your family, one is your friends, the third is your health, and the fourth is your work.” The gist, she said, was that in order to be successful you have to cut off one of your burners. And in order to be really successful you have to cut off two.

Envisioning this symbolic stovetop helps me further reject self-defeating aspirations of a bifurcated work-life balance on a two-sided scale. As I imagine it, with dials to control two big burners and two little ones, just like the real stovetop in my kitchen, this metaphor instead suggests approaching life as an ongoing process of making adjustments. Granted, I don’t think I’ve ever “cut-off” any burners completely or permanently, and I doubt the management seminar leader who cooked up this stovetop idea would deem me “really successful.” But, I think of all four burners as present and available for me to turn up or down in response to life’s challenges, opportunities, demands, and joys.

&fmt=jpg&qlt=90,1&wid=1000&)

My family and me last fall at my sister’s wedding, a month before I had baby #7

This approach makes good sense to me when I think of trying to cook on a literal stovetop—I wouldn’t attempt to make a meal that had four pots boiling away at once. Sometimes, say when I’m writing under a big deadline, I turn up the work burner to high, and I put all other burners down to lower heats. Other times demand that I turn the family burner up high and turn others down low. This was the case last fall when I was my sister’s very pregnant Maid of Honor, and then I gave birth a month later, immediately after which two of my children faced separate, serious medical crises (it was a time, let me tell you).

I admit that at this stage in life, I typically put neither my health nor my friendship burners on high heats. Setting aside their metaphorical dials for a moment to instead envision surface area, I imagine these as the smaller burners on my stovetop, while those bigger ones for work and family are designed to keep the huge stockpots of my current life bubbling away. But, the stovetop analogy has helped me at least name those smaller burners and see them there, ready to get cooking. I do worry that friends will feel I’ve neglected them, or that my health might take a bad turn. But I know well the joy of picking up with someone where we left off with repeated refrains of, “it’s been too long,” and I’m keenly aware of how fortunate I am to be in good health even if I don’t take care of myself the way, say, my mother thinks I should.

Do I have it all figured out? Not in the least! In the acknowledgements for my second book, Reading Picture Books with Children: How to Shake Up Storytime and Get Kids Talking about What They See (Charlesbridge 2015) I thanked a writer I’ve only met in passing, mother-of-five, Donna Jo Napoli, for this sustaining quip I heard her make at a conference many years ago: “How do I do it all? Badly. You could eat off my kitchen floor…for weeks.” I imagine that Lucille Clifton’s kitchen table had some crumbs, proverbial and otherwise, under it, too, and I bet she laughed about them. And if I extend the stovetop metaphor, there have definitely been times when I’ve neglected to adjust dials at necessary moments. Without translating these into specific memories in order to invite you to impose your own, I can admit I’ve had my share of pots boil over, I’ve scorched plenty of pans, and there have been many times when I plain forgot to turn on the kettle.

I realize that time-management challenges, work/life balance issues, stovetop adjustment concerns, or whatever one might call them, aren’t struggles that uniquely impact writing mothers. I also recognize that myriad other aspects of one’s identity and experience can help or hurt one’s ability to do the work of writing. But we writers, all of us, I believe, are impacted by the stories we tell ourselves about our writing lives. Many of those stories, for me, are bound up in the realities of my life as a mother of seven, and I’m better able to be gentle with myself and do the work of writing when I embrace this and try to make those stories aspirational, rather than defeating.

What stories do you tell yourself about your writing life? Are they defeating ones? Inspiring ones? Do they draw on the examples of others in similar circumstances who’ve come before you? Maybe Clifton’s kitchen table will feel more accessible to you than Woolf’s room of one’s own. Maybe Napoli’s humor about her messy kitchen floor will give you relief, too. And maybe you’ll feel empowered by envisioning your life with its many demands as a stovetop with dials you can adjust as you see fit, rather than a teetering scale struggling to balance work and life as separate, competing entities. Or, maybe the stories that work for me in my particular life won’t work for you at all, and that’s ok, too. But, I’d like to hear yours if you can find a moment to pull up a chair at my kitchen table. It’s a mess, but I put the kettle on for tea, and if we can hear each other over my kids clamoring about, I bet we’ll have some good laughs.

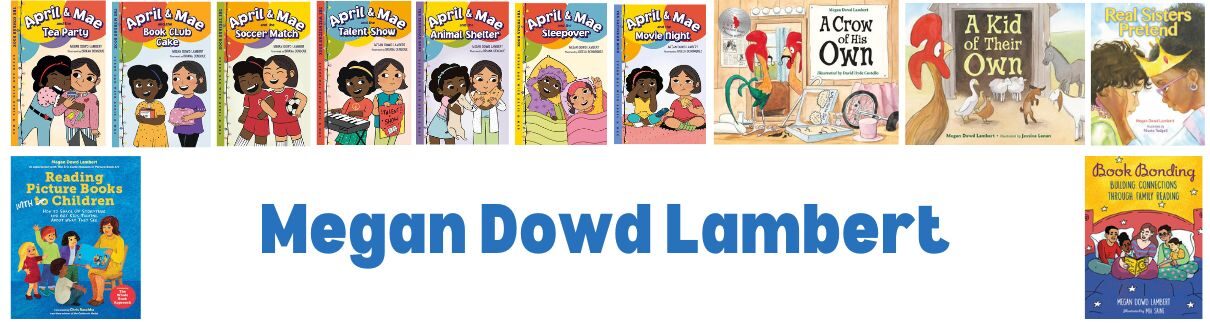

Megan Dowd Lambert, Senior Lecturer in Children’s Literature at Simmons College, is the author of Reading Picture Books with Children: How to Shake Up Storytime and Get Kids Talking About What They See (Charlesbridge 2015), which introduces the Whole Book Approach to storytime that she developed in association with The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art. She received a 2016 Ezra Jack Keats New Writer Honor for her first picture book A Crow of His Own (Charlesbridge 2015) illustrated by David Hyde Costello, and Real Sisters Pretend (Tilbury House 2016) illustrated by Nicole Tadgell, was named a 2017 Notable Social Studies Trade Book for Young People. The mother of seven children ages 0-21, Megan writes and reviews for Kirkus and The Horn Book and lives with her family in Massachusetts. For a PDF of this post, click here.

Megan Dowd Lambert, Senior Lecturer in Children’s Literature at Simmons College, is the author of Reading Picture Books with Children: How to Shake Up Storytime and Get Kids Talking About What They See (Charlesbridge 2015), which introduces the Whole Book Approach to storytime that she developed in association with The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art. She received a 2016 Ezra Jack Keats New Writer Honor for her first picture book A Crow of His Own (Charlesbridge 2015) illustrated by David Hyde Costello, and Real Sisters Pretend (Tilbury House 2016) illustrated by Nicole Tadgell, was named a 2017 Notable Social Studies Trade Book for Young People. The mother of seven children ages 0-21, Megan writes and reviews for Kirkus and The Horn Book and lives with her family in Massachusetts. For a PDF of this post, click here.